Georgia Sagri

What Happens When Performance Art Is Put Up for Sale? - Review

May 4, 2023–May 4, 2023ArtReview

Georgia Sagri brings the invisible labour of artmaking to the fore by highlighting the contradictions of its political economy

Oikonomia in Greek means economy, and kano oikonomia means trying to save money, something most Greeks have painfully practised since the government-debt crisis that began in 2009. In her show Oikonomia, a revisiting of performances from the late 1990s to 2017 and what’s left of them (from damaged and unsold props to memories), Georgia Sagri intelligently reframes ‘saving’ in relation to artmaking and the labour behind it, which is often invisible and unpaid, especially for performance artists. Here, she retrieves old and damaged props and reconceptualises them as an exhibition of wounded objects (curated by George Bekirakis and Danai Giannoglou). Or better, given her longstanding interest in practices of care (which she terms Iasi, Greek for recovery), symbolically ‘mended’ them.

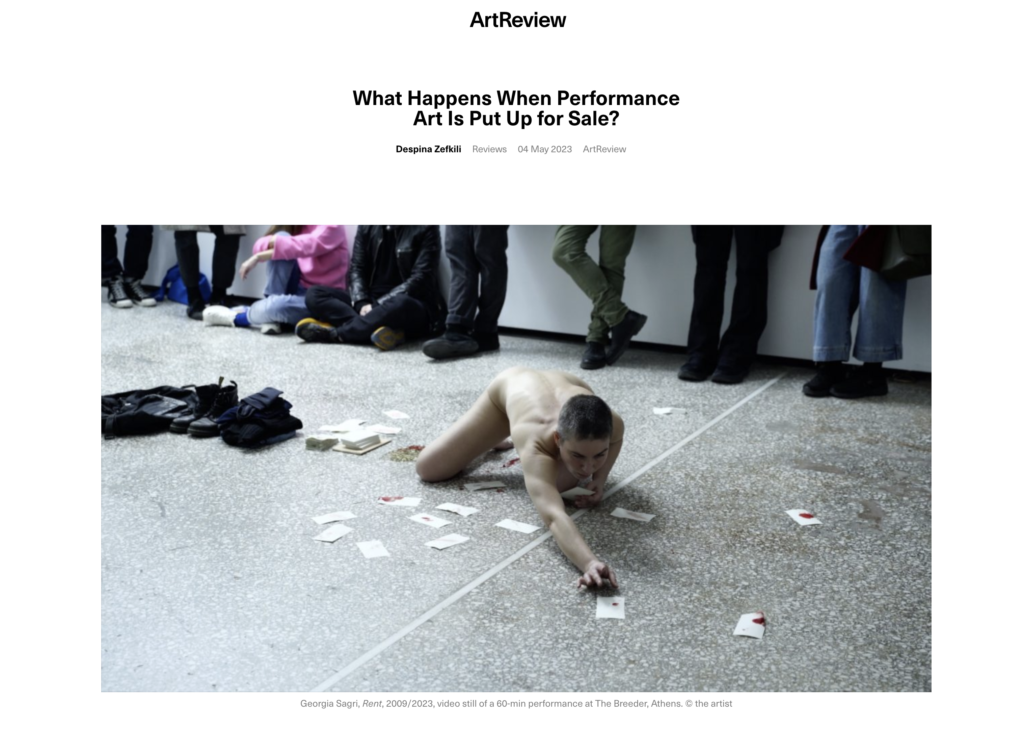

Following a local trend wherein artists reinscribe their work by reworking it, Sagri seemingly comments here on what she calls the ‘pathologies of performance’ in relation to the generalised push towards productivity. The remnants of performance are laid out on carton boxes (Landscape with Diogenes, 2012/ 2023) or dangle from a wooden hanger instead of on the walls where they were originally presented (Breathing Scores, 2017/2023); alongside these are drawings depicting details of said props, and five new typewritten texts comprising poetic recollections of the actions. Moreover, initially live in the gallery and subsequently in videos presented in the show, she tries to reenact three of these works, formerly undocumented. Watching Sagri naked, ‘painting’ banknote-sized papers with her menstrual blood (Rent, 2009/2023) or focusing on her breath for five hours while lying amid debris and gradually creating a pathway within it (Breathing, 2003/2023), is a weird experience: you have to cope with the feeling of experiencing something somehow dated (and echoing first-wave feminist performance art) but also recent.

What I find more interesting amid all this is how Sagri, as a performance artist, highlights the political economy of artworking and visualises its contradictions. While the labour of performance artists and practitioners involved in relational-participatory events has been exploited to expand the accumulation of capital within the artworld with minimum cost, Sagri calls for a redefinition of care for oneself and one’s work in an era where ‘care’ has become a trendy catchphrase for institutions without leading to changes in working conditions in the artworld. In this context, Sagri here does something at once pragmatic and creative. While offering works for sale, she simultaneously foregrounds the market for performance-art documentation, messes with its strictures and reflects on how even performers internalise the necessity of creating saleable objects.